Elusive Traces:

Women in Augsburg

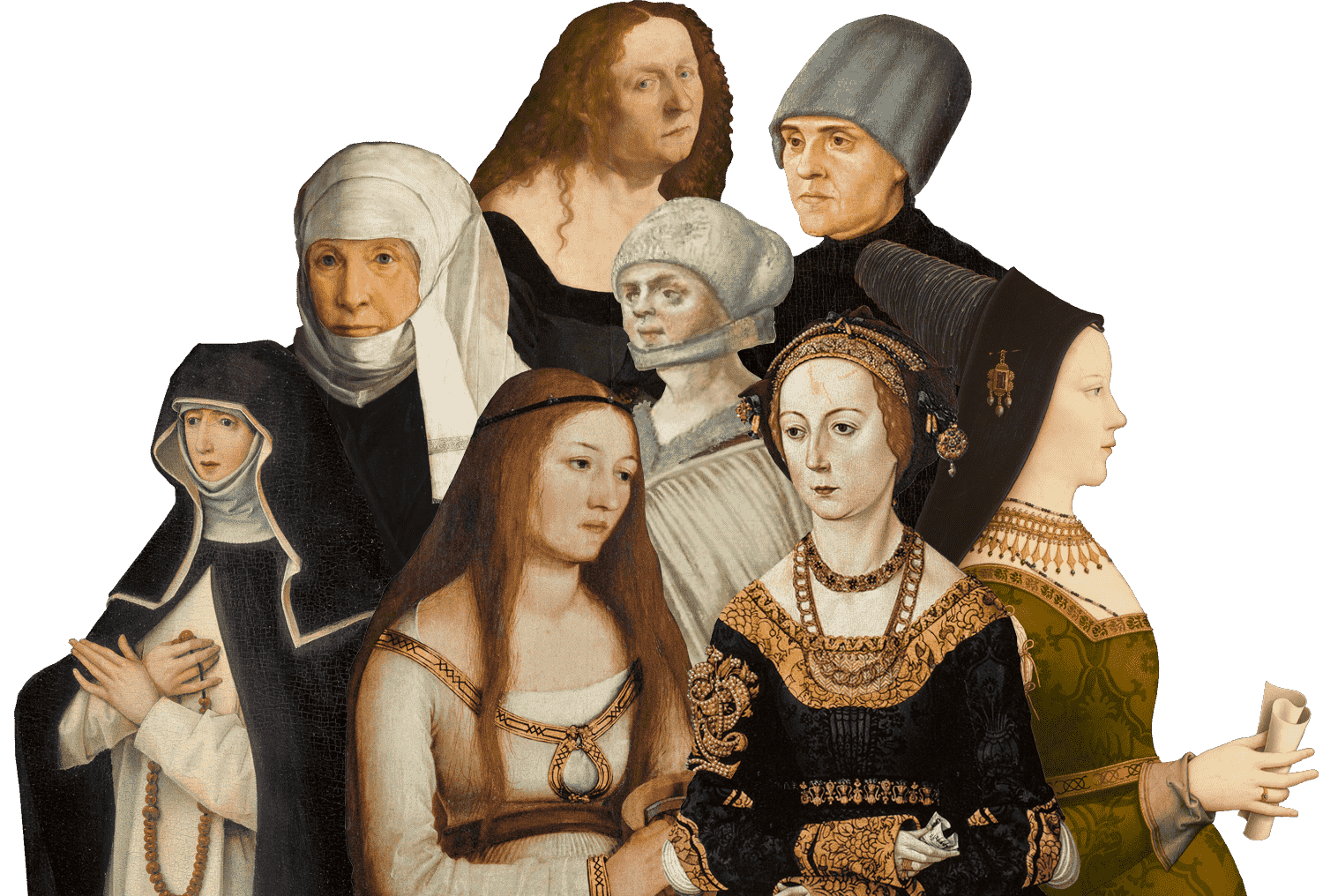

Women have a strong presence in the pictorial world of Augsburg around 1500. Leading artists such as Hans Burgkmair or Hans Holbein the Elder portrayed numerous well-to-do women from the burgher and patrician classes. In the historical sources of the time, however, they have often left only elusive traces. Nonetheless, women played a significant role in the social fabric of the city.

Click on the individuals shown here to learn more about remarkable women who could be encountered in Augsburg around 1500.

A career in the Church – Veronika Welser

(† 1531)

Veronika Welser came from a powerful merchant family. She entered the Dominican convent of St Catherine at a young age. The largest of Augsburg’s convents, it drew many of its members from the patrician class.

From 1504 Veronika was head of the convent, which was extensively renovated and expanded during her period of office. She engaged the foremost painters in Augsburg to decorate the interiors, commissioning Holbein the Elder and Burgkmair as two of the artists to work on the ‘Basilica’ paintings in the chapter house which were dedicated to the seven principal churches in Rome. Donated exclusively by women, these images are associated with a privilege enjoyed by the nuns: through prayer they could obtain the same remission of sins as by an actual pilgrimage to these churches – without having to leave the convent.

With the Reformation turbulent times dawned: numbers dwindled in monasteries and convents; some were attacked, others dissolved. Veronika used the Imperial Diet of 1530 to secure the continued existence of St Catherine’s. In total, four out of eight convents remained in operation throughout the city’s ‘Protestant phase’, whereas all the monasteries were shut down.

Hans Holbein the Elder, Donor Portrait of Veronika Welser c.1504

In the study – Margarete Welser

(1481–1552)

Margarete Welser came from a long-established family with international trade links. She was erudite and very well read. In 1499 she married the scholar Konrad Peutinger. He described Margarete not only as ‘demure, sober-minded, beautiful’, but also as ‘befittingly acquainted with Latin literature’. She is said to have pursued her own scientific interests and to have joined in the discussions when scholars met at their house.

Konrad deliberately showcased his wife’s intelligence, penning a text drawing on antique sources in which the role of the scholar’s wife is discussed. Curiously, he passed it off as a work by Margarete herself. However, it demonstrates an understanding of marriage as a partnership and shows great appreciation for the achievements of his wife, who assumed responsibility for the upbringing of their ten children. Peutinger was also adept at showing off his daughters’ humanist education: Juliana was just four years old when she recited a Latin poem in public, and a letter written by his daughter Konstantia was proudly presented at the Imperial Diet in Worms.

In sixteenth-century Augsburg over thirty per cent of the population could read and write – a comparatively high level of educational attainment. The city boasted more than thirty schools, half of whose pupils were female!

Christoph Amberger, Portrait of Margarete Peutinger, née Welser, 1543

It runs in the family: female masters in Augsburg

This unusual painting shows the artist Hans Burgkmair with his wife Anna Allerlay. We know virtually nothing about Anna. Perhaps she supported Burgkmair in his professional endeavours? As a rule, children certainly helped out from a young age in the paternal workshop.

But unlike their brothers, girls were unable to be trained by their fathers to become masters in the guild of painters – even though around 1500 there were a number of independent female masters in other Augsburg guilds. However, their workshops were far smaller than those of their male fellow-artisans.

Even if women as artists created their own works, they often remained invisible, as attested by the example of the illuminator Magdalena F…: until the death of her husband Narciss Renner, the written sources only document her under his name.

Faint traces – Katharina Schwarz

Loose hair, a yearning gaze, wheel and sword – the sitter is probably Katharina Schwarz, who has here slipped into the role of her patron saint, St Catherine. As with so many women who gaze out at us from the portraits of this time, there is not much in the historical sources to flesh out our knowledge of her.

Her male relatives are far better documented: her father Ulrich the Younger was a wine merchant and innkeeper; her brother Matthäus was Jakob Fugger’s head bookkeeper and known all over town for his exquisite taste in fashion. Katharina’s nephew Hans Schwarz made a name for himself as a medallist.

A votive painting of her father Ulrich also demonstrates how widely ramified the family networks could be in Augsburg: it shows him surrounded by his three wives and thirty-one children. The names of the sons are recorded in the picture, while the girls – except for Katharina – remain anonymous.

Hans Holbein the Elder, Votive Image of Ulrich Schwarz the Younger, c.1508

Hans Holbein the Elder, St Catherine (Portrait of Katharina Schwarz?), c.1509/10

To the manner born – Barbara Bäsinger

(c.1420–1497)

Jörg Breu the Elder (workshop), Portrait of Barbara Fugger (neé Bäsinger) in the Secret Book of Honours of the Fugger Family, 1545–49

The daughter of a goldsmith and mint-master, Barbara Bäsinger married Jakob Fugger the Elder in 1441. The couple had eleven children. When Jakob died, Barbara took over the running of the family enterprise. From the administrative headquarters of the ‘Goldene Schreibstube’ she headed the business for twenty-eight years until her death, succeeding in increasing the Fugger fortune by more than 1,000 per cent!

Barbara’s son Jakob the Rich took the Fuggers’s economic success to another level. He owed the seed capital required for his ventures to his mother’s business acumen. Nevertheless, Jakob decreed that women were no longer allowed to head the business.

Around 1500 several women are recorded as members of the merchants’ guild. Widows in particular, such as Barbara Bäsinger, played an active part in the economy. In respect of the merchant woman, the city statutes stated: ‘Was sie denn tut, das hat wohl kraft’ (‘That which she does, shall stand’). However, over the course of the sixteenth century, women with their own businesses had increasingly less freedom to operate.

Revered and vilified – Anna Laminit

(c.1480–1518)

Anna Laminit’s life seems almost like something out of a film: after being put in the stocks for pimping and driven out of the city as a young woman, she later joined a community of pious women. There she made a name for herself as a ‘living saint’ who took no food and had celestial visions.

Soon Laminit was known far beyond the bounds of Augsburg. She had her devotees at all levels of society, and was revered by Martin Luther, Maximilian I, and his second wife Bianca Maria Sforza. In 1530, prompted by a vision of Laminit’s, the empress even arranged a large penitential procession through Augsburg.

However, the living saint turned out to be a fraud. She ate in secret and misappropriated alms for her own gain. Exposed by Kunigunde, sister of Maximilian, Anna Laminit was expelled from the city in 1514. She then continued her fraudulent practices elsewhere. Abandoned by fortune, she was eventually convicted and executed in 1518.

Hans Burgkmair the Elder, Portrait of Anna Laminit, 1502/03

Till death us do part – Sibylla Artzt

(c.1480–1546)

Hans Burgkmair the Elder (?), Portrait of Jakob Fugger and Sibylla Artzt, 1498

Sibylla Artzt married Jakob Fugger the Rich when she was just eighteen. It was probably not just her youth and beauty that attracted the merchant, who was already thirty-nine.

Marriage to Sibylla, daughter of one of Augsburg’s most respected families, brought social advancement, gaining Jakob admission to the ‘Herrenstube’, an exclusive meeting place of influential individuals. The marriage remained childless, and Jakob’s nephews were designated as heirs to the business.

Little is known about the couple’s life together. However, a number of sources report on their separation. After Jakob died in 1525, there was a veritable éclat when only seven weeks later Sibylla converted to Protestantism and married the patrician Konrad Rehlinger. Jakob’s estate had to be settled in court, where Sibylla broke off relations for good with the Fuggers. This is also attested to by her will, in which her first husband – contrary to the custom of the times – is not mentioned at all.

Hotly contested – Maria von Burgund

(1457–1482)

Niklas Reiser (?), Portrait of Mary of Burgundy, c.1500

The first time her hand in marriage was sought, Mary of Burgundy was just five years old. Like many daughters of the nobility, she was a pawn in the struggle for political power. The Habsburgs also conducted marriage negotiations with Mary’s father, Charles the Bold – at first without success.

When Charles died unexpectedly in 1477, Mary was his sole heir. As a woman, she had to defend her claim to power against huge opposition. In this she was supported by her step-mother Margaret of York. In the face of an impending war of succession with France, she decided to marry Maximilian I. The marriage was of only brief duration: following a riding accident the Burgundian duchess died aged just twenty-five.

Although Mary never visited Augsburg, she could be encountered there: At Maximilian’s behest she was memorialized in numerous pictorial works, such as Theuerdank. The reasons for this were not purely sentimental: in this way the House of Habsburg was emphasizing its role as heir to Burgundy.

Picture captions

Hans Holbein the Elder, Donor Portrait of Veronika Welser, c.1504. Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen – Staatsgalerie in der Katharinenkirche Augsburg

Christoph Amberger, Portrait of Margarete Peutinger, née Welser, 1543. Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen – Staatsgalerie in der Katharinenkirche Augsburg

Laux (Lucas) Furtenagel, Portrait of Hans Burgkmair the Elder and his wife Anna, 1529. © KHM-Museumsverband

Hans Holbein the Elder, St Catherine (Portrait of Katharina Schwarz?), c.1509/10. Gotha, Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein

Jörg Breu the Elder (workshop), Portrait of Barbara Fugger (neé Bäsinger) in the Secret Book of Honours of the Fugger Family, 1545–49. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

Hans Burgkmair the Elder, Portrait of Anna Laminit, 1502/03. Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum

Hans Burgkmair the Elder (?), Portrait of Jakob Fugger and Sibylla Artzt, 1498. Schroder Collection on permanent loan to the Holburne Museum, Bath

Niklas Reiser (?), Portrait of Mary of Burgundy, c.1500 © KHM-Museumsverband