Boom town

Augsburg

A centre of the Renaissance

north of the Alps:

history, money, and politics

Augsburg’s central location on established trade routes enabled it to develop into an important commercial city. Its new wealth led to an incomparable cultural flowering. As a ‘free imperial city’ Augsburg was subject only to the emperor himself. Numerous imperial diets were held there at which the emperor met with rulers and princes from throughout the empire to engage in consultations.

Important political decisions were made here – and important art was produced.

Unknown sculptor, Neptune, c.1536

Renaissance in the North

Artistically minded trading houses such as that of the Fuggers cultivated international contacts that brought numerous Italian works of art to the city.

As a result, awareness of the new art and culture of the Italian Renaissance arrived in Augsburg earlier than in all other cities north of the Alps and had a more lasting impact.

This suited how the Augsburgers saw themselves: as Augsburg had been founded by the ancient Romans, they were ‘Roman’.

Lorenz Helmschmid, Field armour for the later emperor Maximilian I, c.1485

Old becomes new

From the fifteenth century onwards Augsburg was a centre of armoury, the art of making suits of armour and weapons.

While this harness made for the later Emperor Maximilian I is still entirely Gothic in terms of its aesthetic ideals, the bronze figure of Neptune, the classical sea-god, is clearly a Renaissance work of art and very modern for its time. It was one of the first post-classical naked figures to be put on public display. It embodies an enthusiasm for antiquity while also representing a departure from Catholic veneration of the saints.

Jörg Seld/Hans Weiditz (?), Bird's-eye view of the city of Augsburg from the west, 1521

Augsburg

Metropolis with global businesses

In the years around 1500 Augsburg was one of the most important

economic and cultural centres north of the Alps.

This was due to the city’s favourable geographical location and, above all, to the close ties between Emperor Maximilian I and the Augsburg trading houses, especially that of the Fuggers. They gave the ruler loans to finance the imperial diets and military campaigns, and in return they were able to exert influence on imperial politics.

The city’s growing prosperity attracted increasing numbers of merchant families, who also became involved in the voyages outside Europe, thus profiting from the trade in ‘exotic’ goods and spices.

The city has exceedingly fine buildings, and broad, clean streets …

Matthias Quad, Teutscher Nation Herligkeit, 1609

Jörg Bräu the Younger and workshop, Entry of the six spokesmen of the crafts into Augsburg City Council in 1368 1545

(Cim 21), fol. 37r

Guilds

Augsburg’s municipal administration was regulated by the constitution of the city council, for which the ancient Roman Republic served as a model.

Craftsmen were organized in guilds that under the ‘guilds constitution’ had a political say and exercised power over production and trade. This was an institution of the imperial city with a centuries-old tradition. It was abolished by Emperor Charles V in 1548.

A new way of thinking for a new era

The power of scholars

One particular characteristic of the Renaissance is humanism, an educational movement which, by combining knowledge with virtue, sought to develop a person’s abilities to the greatest possible extent. The adherents of this new movement strove to lead an ideal existence by imitating models from classical antiquity.

Humanist research and collections were in evidence in Augsburg at an early stage. The city’s marked enthusiasm for education and intellectual renewal was largely brought about by the Italian-influenced Konrad Peutinger. He encouraged the collecting of Roman coins, stone monuments, documents, and other historical sources. He also assisted with and coordinated Emperor Maximilian I’s ambitious book projects.

The atmosphere of intellectual enquiry attracted important scholars to the city after 1500. Knowledge of Latin, Greek and Hebrew was needed to read ancient writings. Augsburg printing houses published numerous translations of texts by Italian authors.

Konrad Peutinger

Konrad Peutinger was one of the key figures of Augsburg humanism. Trained as a lawyer in Italy, he was a counsellor to Emperor Maximilian I and owned one of the largest libraries north of the Alps. He studied Latin inscriptions and was an avid collector, whose collections included Italian works of art and classical Roman coins.

| Born | 1465, Augsburg, Germany |

| Died | 1547, Augsburg, Germany |

| Eltern | Conrad Peutinger, Barbara Frickinger |

| Partner | Margarete Welser |

| Children | at least eight children, one of whom, Juliana Peutinger, recited a poem in Latin to Maximilian I at the age of only four |

Hans Schwarz, Portrait medal of Konrad Peutinger, c.1517/18

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Coin Collection, inv. 476bß © KHM-Museumsverband, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

Money makes the world go round

The power of money

Heinrich Vogtherr the Elder, Labour of the Month with the Perlach Tower and Augsburg City Hall, c.1540

As a centre of trade and diplomacy,

Augsburg offered merchants numerous opportunities.

The Fuggers and the Welsers were among the most influential and wealthy families not just in the city of Augsburg but in the whole of Europe. Their names became synonymous with wealth and political influence acquired through success in business.

Denn wer hat,

dem wird gegeben werden…

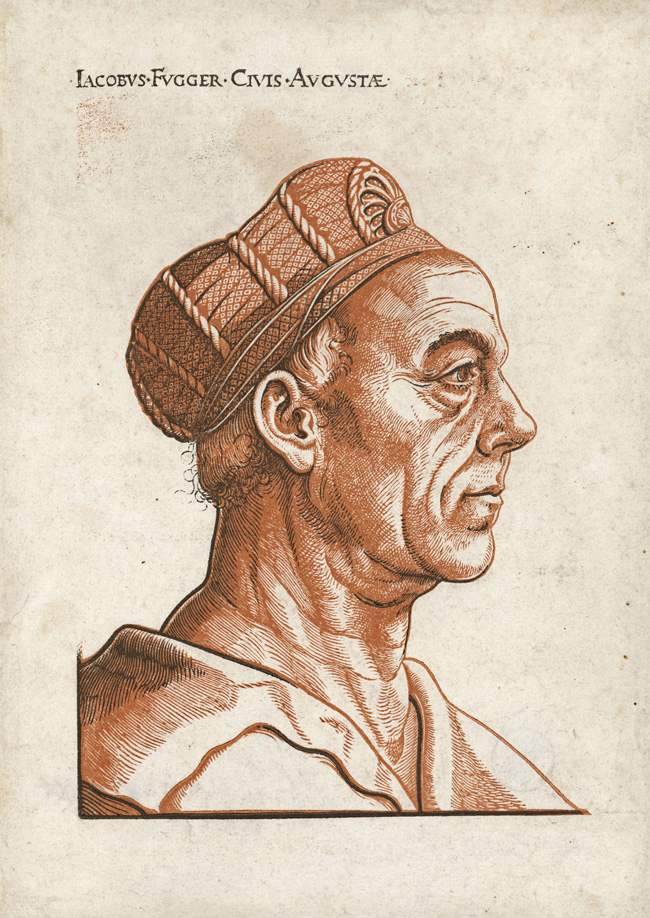

Hans Burgkmair the Elder, Portrait of Jakob Fugger, c.1518

A powerful family business

Originally weavers, the Fuggers rose economically and socially to create the most important mercantile business of their time. As well as establishing an international trading network, they were also active in the lucrative area of mining and smelting.

Using modern Italian accounting practices as their model they granted loans that enabled them to exert political influence on Habsburg emperors from Frederick III through Maximilian I to Charles V. After the Habsburgs, their most important clients were the curia of the Roman Catholic Church and its dignitaries north of the Alps.

Painted three hundred years after the death of the persons depicted in it, this picture represents a romanticized nineteenth-century view of how the economy and politics worked. It shows a member of the Fugger family burning the promissory notes issued by Emperor Charles V.

The Habsburgs were grateful borrowers from the Fuggers. The remissions of debts depicted here was not so much a demonstration of friendship but rather a carefully calculated investment on the part of the Fuggers, that would allow them to exert political influence on the emperor. This was preceded by hard bargaining to protect the Fuggers’ business interests. In return for the cancellation of part of his debts the emperor had to grant the Fuggers extensive freedoms.

In this picture the painter Carl Ludwig Friedrich Becker (1820–1900) uses elements borrowed from sixteenth-century paintings. The figure of Charles V, for instance, recalls Jakob Seisenegger’s famous portrait of the Emperor in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, while the young lady who is bringing the monarch a costly beaker of wine is a quote from a picture by Hans Holbein.

Money and art

Following the example of the nobility, the Fuggers played a leading role as patrons of the arts and made an important contribution to the cultural flowering of the city of Augsburg and the German Renaissance.