Artistic updates

Augsburg was where the first German portrait medals were made and also where new printing techniques such as the colour or ‘chiaroscuro’ woodcut were invented or perfected. The small relief also enjoyed its heyday in Augsburg.

Hans Burgkmair was prominent in many of these fields: he was a pioneer of the colour woodcut and one of the first artists north of the Alps to use red chalk as a medium for drawing. He also created exciting mythological depictions and a number of the first detailed drawings of peoples from outside Europe.

Portrait medals

Hans Schwarz, Portrait medal of Konrad Peutinger, c.1517/18

Hans Schwarz, Portrait medal of Albrecht Dürer, 1520

The humanist Konrad Peutinger played an important role in establishing the (portrait) medal north of the Alps, a genre that had been popular in Italy since the mid-fifteenth century. Based on portraits seen on Roman coins, medals of this type were made by the Augsburg medailleur Hans Schwarz and typically show heads in profile – in this case the heads of Dürer and of Peutinger himself.

In 1518, Albrecht Dürer was in Augsburg for the imperial diet and made a portrait drawing of Hans Burgkmair. Perhaps Burgkmair used this opportunity to show him his new portrait medal. Dürer later also designed a portrait medal for himself, which he had made by Hans Schwarz.

The persons depicted are shown in profile, like Roman emperors. An inscription in Latin tells us their names and social rank. Despite the medals’ small size, additional motifs can convey complex information.

Iron-plate etchings

Kolman Helmschmid etched decoration attributed to Daniel Hopfer, Armour, presumably made for Bernhard Meuting, c.1525

Kolman Helmschmid etched decoration attributed to Daniel Hopfer, Armour, presumably made for Bernhard Meuting, c.1525 Vienna

Kolman Helmschmid was the son of Lorenz Helmschmid, who had made the Late Gothic harness for Emperor Maximilian I. Around four decades later Kolman produced the armour shown here for an Augsburg patrician.

In this harness, Renaissance fashion ideals replace those of the Late Gothic. Daniel Hopfer’s etched decoration of the armour is especially interesting. To decorate the steel a chemical process was used. First, the surface was given an acid-resistant coating, with the pattern either being left uncoated or scratched into the coating with a pointed needle. The etching acid then ate into the uncoated areas of metal. The pattern, which had a certain depth, was then coloured black.

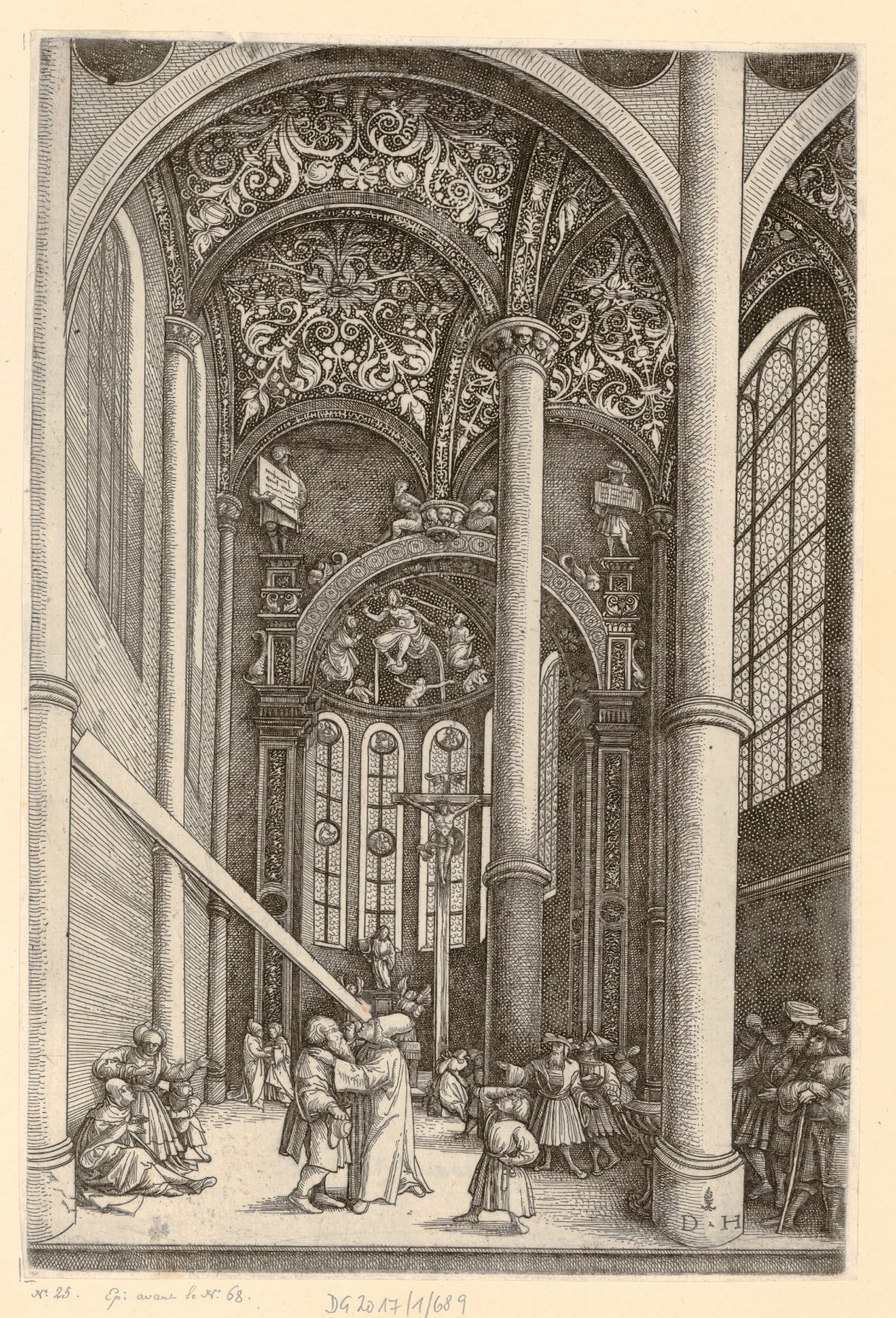

Daniel Hopfer, Interior View of the Dominican Church with the Parable of the Mote and the Beam, c. 1530

In Augsburg, artists and armourers belonged to the same guild, and several artists used this close connection to work in both professions. Daniel Hopfer, who made etched decoration on armour, used the same technique to etch iron plates from which prints were then made, thus inventing the iron-plate etching. Hopfer depicted the Dominican convent church in Augsburg using this new technique.

The print is one of the earliest autonomous architectural views in German graphic art.

Printed colour

The colour woodcut showing the crucifixion of Christ belongs to the established tradition of liturgical books. It is the earliest work by Burgkmair in the exhibition.

Burgkmair also introduced new elements to the young medium of book printing:

although there were established norms for liturgical books, he depicted space, bodies, and surfaces in an increasingly realistic manner. He learned the technical skills needed to produce a colour woodcut while working with the Augsburg printer Erhard Ratdolt. In this process, instead of the black outlines being coloured in by hand, the colours are printed using one or more tone blocks.

Hans Burgkmair the Elder, Crucifixion (canon illustration), 1494

red, blue, yellow, and green, flesh tints and sky hand-coloured, on

parchment, 252 x 163 mm (block). Vienna, Albertina, inv. DG 1930/50 © Albertina

Hans Burgkmair the Elder, Lovers Surprised by Death, 1510

Hans Burgkmair tried out the new techniques of gold and colour woodcut printing, both requiring the use of multiple separate printing blocks. The woodcut Lovers Surprised by Death is one of Burgkmair’s masterpieces and a major work of the German Renaissance.

Nowhere else does the artist demonstrate his dramatic skills quite so clearly, and never again was he so successful in combining figures with a background of Italian architecture. This technically brilliant print is the first example of a colour woodcut printed with three blocks.

The dramatic scene of Death surprising the lovers is also the first woodcut in which the printed areas of colour create the effect of light and dark painting. While the backdrop is completely Italian, the allegory of Death and the ‘memento mori’ overtones place the work clearly in the German tradition.

New themes in

drawings and prints

Shortly after 1500, Augsburg merchants became involved in the Portuguese voyages of conquest. Thanks to its favourable geographical location near the Alpine passes and the connection to the European trade routes, Augsburg became a hub for goods and novelties from all over the world.

Knowledge from the different parts of the globe reached the imperial free city, attracting both scholars and artists.

Albrecht Dürer, The Rhinoceros, 1515

![[Translate to English:] Hans Burgkmair d.Ä., <em>Das Rhinozeros</em>, 1515, Holzschnitt, 224 × 317 mm](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/a/csm_1_17_RN_207_DG1934_123_Hans_Burgkmair_Das_Rhinozerus__878fdd22db.jpg)

[Translate to English:] Hans Burgkmair d.Ä., Das Rhinozeros, 1515, Holzschnitt, 224 × 317 mm

North of the Alps, increasing numbers of autonomous drawings were made after 1500. No longer serving as preparatory studies for a (usually) religious work, they often reflect artists’ interest in the world around them.

On 20 May 1515, there was a sensational event in Lisbon that had an impact throughout Europe: King Manuel I received a gift of an Indian rhinoceros.

News of this exotic beast spread rapidly, accompanied by an illustration. In the same year, Albrecht Dürer in Nuremberg used the illustration to make a pen-and-ink drawing and a woodcut. Around the same time as it reached Nuremberg, news of the rhino must also have arrived in the rival city of Augsburg. A short time later that same year, Hans Burgkmair likewise designed a woodcut of the rhinoceros.

Pictures of the ‘Other’

Hans Burgkmair the Elder, The King of Cochin with Retinue (woodcuts from Balthasar Springer’s Indian expedition of 1505), 1508

These were the most influential prints depicting – to Europeans – ‘unknown’ peoples who lived along the coasts of Africa and eastern India. Burgkmair’s woodcuts were long held to be the first images to show an ethnographical interest in non-European peoples.

The nakedness of the figures in such depictions illustrates a highly problematic tradition, because their aim was clearly to depict a ‘primitive’ culture. While in his woodcuts the artist was striving for authenticity, ultimately these illustrations reflect stereotypes such as that of the uncivilized ‘Wild People’. Later, depictions of this kind were to be used to justify the exploitation of cultures outside Europe. They thus mark the beginnings of a colonial frame of mind and eye that would long prevail in Europe.

The period also saw depictions of ethnic groups from outside Europe beginning to appear in Augsburg. Around 1503, news of ‘discoveries’ made in the course of Portuguese colonization became more frequent.

As trading houses in Augsburg and Nuremberg were keen to seize a share in the new and highly lucrative business opportunities, they financed expeditions. Through Konrad Peutinger’s connections, Hans Burgkmair was commissioned to design an opulent pictorial frieze as illustration to a highly successful travelogue printed in 1508: the depictions of the King of Gutzin (Kochin) and his retinue are evidence of a globalizing world in which Augsburg was an important hub.

Renaissance imports

The newly erected Fugger Chapel was the first proper Renaissance building north of the Alps.

Most likely inspired by this chapel, the Duke of Saxony commissioned Adolf Daucher’s workshop to make a portal employing similar forms for the cathedral at Meissen.

This page clad in antique armour and holding a shield with the coat of arms of the Dukes of Saxony once formed part of this portal. Comparable shield-bearers are found on fifteenth-century Italian tombs. Through such pieces made in Augsburg using imported ideas, new southern themes and forms also spread to other areas north of the Alps. Given that putti, small boys either naked or sparsely clothed, were previously unknown, Hans Daucher can be said to have introduced a new canon of forms to early Renaissance sculpture in Augsburg.

Hans Daucher, Shield Bearer from the portal of the Ducal Chapel of Meissen Cathedral , 1520/21

Expanding the market

It was not just artists who showed an interest in new forms, styles, and themes and in the developing technical possibilities further.

The world view, wishes, and expectations of their clients also changed.

Artists were increasingly appreciated on account of their abilities to adapt to new developments. The sciences, which were beginning to flourish, also required the artist’s input to depict all that had been discovered and researched.

Increasingly, artists left the image of the pure artisan behind them, becoming exploratory, constantly searching creators who were admired for their technical and intellectual mastery.